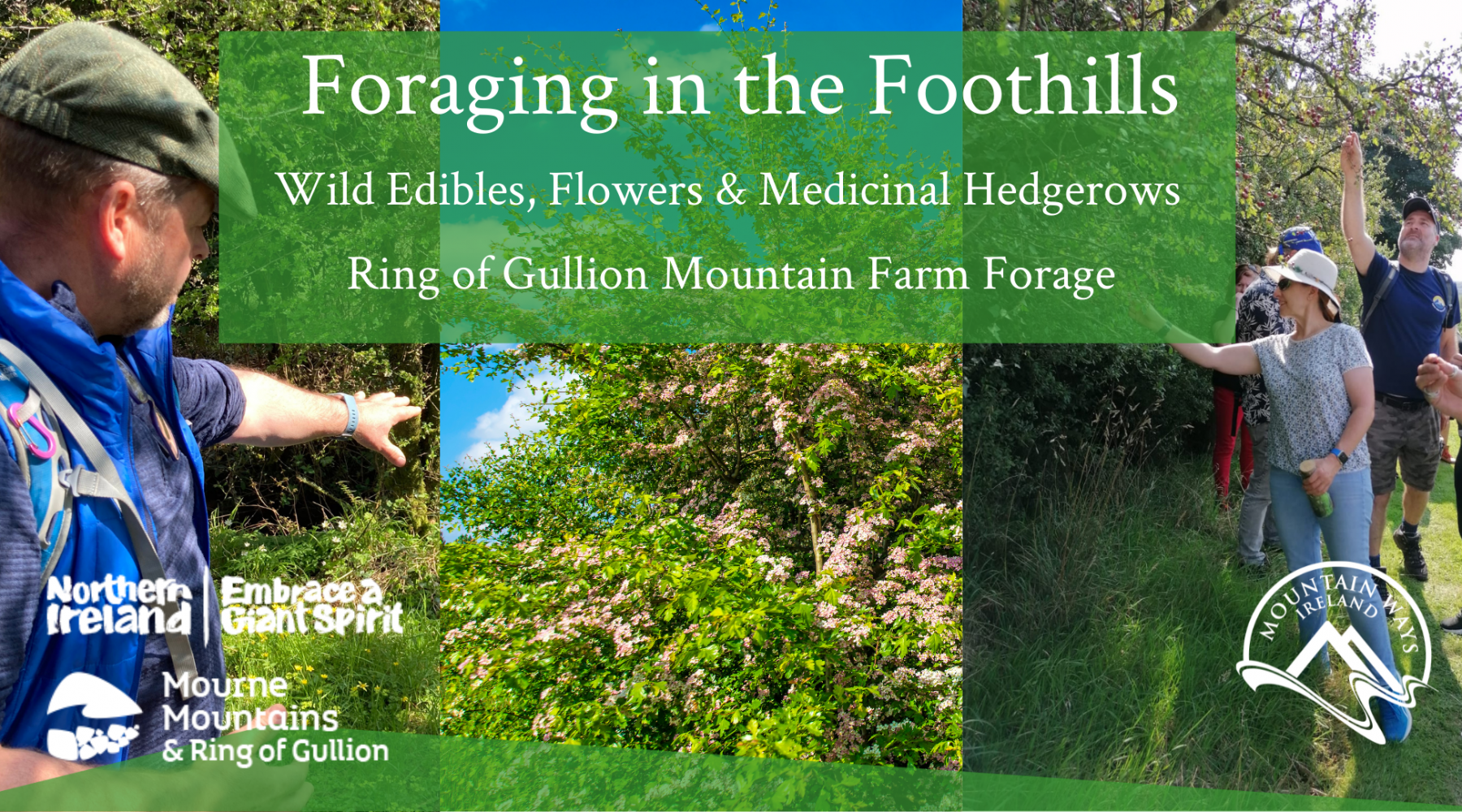

Foraging isn’t a word that I particularly like but it’s the one that is mostly in use nowadays to describe something that was second nature to our ancestors. The gathering and use of wild edibles, medicinal plants, herbs, trees, mosses, lichen, fungi, and whatever else nature has to offer. When we were children we didn’t call it foraging. We went ‘picking’ blackberries. Why the title ‘Foraging in the Foothills’, you may ask, why Foraging in Ireland? … well, because I am blessed to live on the lower slopes of one of Ireland’s most mystical mountains, Slieve Gullion in County Armagh. Foraging in the Foothills is the name of a seasonal ‘introduction to foraging course’, or experience that I deliver from my own home and ancestral farm. This article hopefully goes some way to explain that, for me at least, it is so much more than a simple plant identification walk.

Foraging and Farming in The Ring of Gullion

These foothills in the Ring of Gullion, South Armagh area are where I search out nature’s wild larder. I find ‘weeds’ on the field margins, the hedgerows, the rough corners, and ‘semi-wild places’. The very few remaining pockets of old-growth forest are a treasure trove for the forager. Those precious areas have escaped the onward march of monoculture farming practices that have shaped our modern landscape. Let’s not forget about the state-sponsored practice of monoculture commercial forestry and clear-felling desecration of our mountain slopes.

Just to be clear, before you think I’m going to begin blaming small farmers for the world’s ills, I’m not. I come from a long line of farmers. Family records can only go back a few hundred years but when I look through my back door up towards the highest surviving passage tomb in Ireland, I see The ‘Cailleach Beara’s house’. I feel a deep connection with those who built this stone monument on Slieve Gullions summit around 6,000 years ago. After all, these Neolithic people were farmers also, the first farmers to live in my homeplace.

Foraging, Farming and the Changing Landscape

It’s worth saying a couple of things about the politics of farming practices, without going down a rabbit hole. My ancestors in the last few centuries and up until very recently were working on small upland plots of land, scratching a survival among rocks, whin, bracken and heather. Famine was a constant danger. They struggled lower down the valley in boggy marginal land trying to feed their families. Foraging for them was a part of their everyday existence. My Grandfather, Barney Hoey, born in 1899 told me about eating the ‘blaeberries’ as children. These grew on the ditches up towards the mountain. They were a delicious treat especially for people who knew what hunger felt like, unlike most of us nowadays.

I remember the generous government grants encouraging the clearance of upland areas, draining of bogs, removal of centuries-old ditches and hedgerows. These same bodies destroyed the built heritage. They forced the destruction of old vernacular cottages before allowing a replacement dwelling. Things have now come full circle where the same farming families are financially penalized for habitat destruction and are being actively encouraged to ‘re-wild’. This is a move in the right direction but hard to swallow when we look at the desecration of our mountain landscapes caused by commercial forestry.

Those policymakers and forestry commission continue the destructive cycle of clear – felling and replanting vast swathes of non-native trees with a token gesture percentage of broadleaf natives thrown in.

What has this to do with foraging? The answer is everything because we all need wild places whether we realize it or not!

How do I learn How to Forage ?

How do I personally know what to forage, what is tasty, nutritional, or what is purely medicinal? Where do you begin to learn what is harmful, dangerous, or absolutely poisonous? The truth for most people foraging in Ireland today (including myself) is that invariably a lot of the information has come from books. Books are great but they are just a starting or a reference point.

There is nothing to beat walking in nature and learning first-hand from other skilled practitioners. Eventually, a really in-depth understanding only comes from you yourself observing nature and specific plants through the changing seasons. You have to engage all of the senses; touching, smelling, listening, and finally tasting edible plants. This takes time and years of experience.

More recently, the pervasion of the world wide web and internet has served to spread knowledge wide and far. However, I always cross-check information, no matter where it comes from but even more so the online stuff. The stakes are simply too high and there is too much misinformation or half-knowledge out there. So, simply put most of the foraging knowledge is about re-connection rather than a direct line of knowledge.

Foraging Fungi in Ireland

Some people are lucky enough to retain some of that first-hand oral tradition. The direct link is handed down from the older generations, even if it is something very small, then at least the connection isn’t broken. It’s worth saying that many people living in Ireland today who are originally of Eastern European extraction do come from cultures where they have learned first-hand a knowledge of foraging. This is particularly true of fungi. Most Northern European cultures don’t have that connection.

Anyone who has looked into the history and heritage of foraging in Ireland will understand that even though my generation ‘picked’ blackberries, gooseberries, blaeberries, and a few other delicious wild edible treats – when it came to mushrooms we left them be. There was a general fear of the fungi kingdom. In folklore, mushrooms were associated with the other dimension, with fairies, pookas, goblins.

In broad terms, when it comes to mushrooms and fungi, it’s widely accepted that worldwide, cultures are broken down into two groups, the Mycophobic i.e., those that are fearful or mistrustful of the fungal kingdom and those that are the opposite, the Mycophilic. Ireland in common with The UK and many Northern European countries has been for many centuries a largely ‘mycophobic’ society. Some suggest that this fear or mistrust goes back a lot further and that The Celts were mycophobic but, personally, I remain to be convinced of that.

Annie Mc Coy

It has always fascinated me to think about my aunt, Annie Mc Coy, and how she knew how to gather mushrooms for the table from the fields high up on her hillside farm. I have a vivid memory as a child when she gave my uncle some mushrooms that she had just picked from the fields earlier that morning. I don’t recall for one second any sense of hesitancy on his behalf. They may have been common field mushrooms but almost 40 years later I can’t be sure. Even at that, how did she know how to distinguish them from the very similar but poisonous ‘yellow stainer’? Who taught her that? Why was one small ‘Agaricus’ family member passed on through the narrative as edible while many, many ‘good eaters’ weren’t? So many questions are left unanswered!

Unfortunately, it’s too late for me to ask her the simple question, “how do you know which one to pick and more importantly which should be left alone”? Knowing Annie, there would have been a very witty answer! One thing for sure, it didn’t come from a book; it was something handed down orally from a much older and deeper fountain of wisdom.

Annie ‘Robin’ Mc Guill

I have a lovely anecdote that ties the loss of our connection to nature with the equally heart-breaking demise of the native Irish language in Ireland. Both of these facets of our heritage and culture were relegated to the margins. The two go hand in hand because the loss of a language cuts much deeper than a method of communication. There is a well-known Gaelic Proverb, ‘Tír gan Teanga, Tír gan Anam’ – ‘A land without a language is a land without a soul’. The playwright, Brian Friel explored this beautifully in his play, Translations.

One day in the late summer, I was walking with my father on the ‘Cargas’, a beautiful upland part of our farm when we came across a few grassland mushrooms. Almost just as an aside he said that his granny, Annie ‘Robin’ McGuill always told him to leave them alone because they were ‘oul ‘Bakanbarras’ or ‘Bakkanberrys’. The phrase imparts an undertone that they are no good. He had no idea what it meant beyond the term itself and what it referred to. My father was born almost twenty years after his sister Annie Mc Coy who by that time had passed away, so I couldn’t ask her.

Foraging and the Irish Language

My Irish is very rusty and although I didn’t know what it meant, I immediately knew that the term ‘bakkanbarra’ was rooted in the native tongue. The very fields where they grow have Irish names, preserved among our family and neighbours up until today. We call these fields, The ‘Cargas’ coming from the Gaelic term for rocks, ‘na carraigeacha’. These terms are the last remnants of the beautiful everyday language spoken in this townland for thousands of years. I also knew that the term was rooted in that ancient knowledge of the natural world.

Like the language, the deep connection to nature was handed down orally from one generation to the next. This passing on of wisdom didn’t happen over centuries but for thousands of years. There is little doubt that for those Neolithic and later Celtic peoples, the natural world, the night sky, and the universe were all interconnected. The spiritual dimension and the natural growth cycle of life intertwined and blended as one.

Getting back to the digital reality of my world today, the first port of call to search for the word ‘Bakanbarra’ was trusty google. It was disappointing to find that this all-seeing guru had no answer. I took my old tattered ‘O Dónaill’ Irish dictionary down from the shelf. I began to search working on the assumption that the term was something bad or poisonous. After a while, looking, I came up with nothing. It went off my radar and I left it for another day.

Annie Mc Donnell

A few weeks later I was leading a guided tour on the same Cargas. There was still a flush of mushrooms at exactly the same spot. As we stood there, a cousin of mine who was among the group began to share a story. He told us about his grandmother, Annie Mc Donnell from the townland of Aughanduff in South Armagh. Peter told us that she used to call them ‘Bakanbarrras’.

I was gobsmacked!

Folklore has been a passion of mine for years. I have collected, old Gaelic field names, placenames, sayings, etc. since I was at school but in 50 years had never heard the term. I recorded some of the old people of the area, some of whom had been born in the 19th Century and the word never came up.

Now I had heard it twice within a month, from two different people, standing at the same gateway, looking at the same area of mushrooms!

If that’s not a message of sorts, I don’t know what is.

That same evening, I again turned to Ó Dónaill.

Like most things in life the explanation was very simple and stared me straight in the face.

There are a few different words for mushroom in the Irish language, one that may be more commonly used today is ‘muisiriúin’. That word-initially threw me. Then I found another word.

‘Beacán’ also means mushroom in the Irish language.

And then there it was…

Beacán Bearraigh – a Toad Stool ( Bakanbarra)

It’s worth saying that my father doesn’t speak Irish and knows very little about wild mushrooms. However, on that day while I was more interested in what species we were looking at, he had more Irish and a closer link to the ‘old ways’ than I did.

A lesson from the Past

The message for me couldn’t have been clearer. The language like the knowledge of the natural world hangs on in small pockets, it perseveres in our fabric, it’s there just below the surface. Thankfully, both are undergoing a revival in recent years. The Irish language in South Armagh, like many other parts of Ulster, flourishes. Likewise, there is a strong revival in foraging. Foraging is only one part of the wider re-connection with ancestral wisdom and skillsets. The land is drawing people back and if this recent upheaval in society worldwide has done nothing else, it has made people look closer at their existence on this planet and think about what is really important in life.

For one thing, people more than ever are looking at their food and asking questions. What’s in it ? Where does it come from? How come its so colourful but tastes of nothing? What do those numbers on the side mean? Does everything need to be pasteurized and why does it have to be packaged like that?

Foraging in Ireland is part of our Culture

When I lead a foraging walk, I hope that in some small way, I keep part of our heritage and culture alive for the next generation. Language, sport, music, song, dance, and crafts are all well recognised as being intrinsic to the Gaelic culture. What could be more important than understanding how to live in closer harmony with the natural world around us, just as our ancestors did. What could be more central to a culture than their food? Is there anything more important than the ‘cures’ and medicine?

We should remember which plants to use medicinally, not depend totally on pharmaceutical giants. We should be able to recognise ‘wild food for free’. These gifts are rich in both macro and micro-nutrients way beyond their bland, tasteless descendants found on the shelves of supermarkets.

At times I refer to edible and medicinal as two separate entities. I do this merely to distinguish some wild gifts from nature which definitely should only ever be applied externally. However, our ancestors understood implicitly that broadly speaking ‘food is medicine and medicine is food’.

Whispers through the Generations

On that day, with my father, by a gateway into the ‘Cargas’, my great grandmother, Annie ‘Robin’ passed that knowledge on to me, even though I never met her. She was born in 1882 and died in 1964, four years before I was born. Those couple of encounters on a Slieve Gullion slope spurred me on to visit my aunts again and ask simple questions. I’ve since found other golden nuggets of plant knowledge directly passed down through our family. These direct links to the past, no matter how insignificant they seem are absolutely precious. They are worth a thousand books.

That’s what ‘Foraging in The Foothills’ is about for me. It’s much, much more than learning what I can or cannot eat. Although the knowledge that will keep me safe foraging is extremely important, it’s more than finding out what is medicinal, what will nourish, and what will kill. Foraging is a living but intangible connection to my ancestors. Those ancestors survived the Great Irish Famine of the 1800’s and left behind their famine ‘rigs’ on the Cargas. Those ancestors who built the ‘Cailleach Bearra’s’ House or Neolithic tomb on Slieve Gullion’s summit almost 6,000 years ago.

Micheal J. Murphy and Mushrooms

Almost as a footnote, one of the great mysteries for me is this; Micheal J. Murphy was one of, if not, the most prolific folklore collectors in Ireland during the 20th century. In 1961, Seán Ó Súilleabháin of the Irish Folklore Commission asked Micheal J. along with six other collectors to search out whatever information they could about mushrooms. They all began collecting in their own local areas, whatever was known specifically about mushrooms.

Micheal J. was a close neighbour of mine, from the same parish in fact, and he reported back to the folklore commission in Dublin. He told them that after completing a detailed investigation through South Armagh and Omeath in County Louth, he had very little positive data to report. He couldn’t even find any names known for them in Irish. I honestly don’t understand this. Micheal J. Murphy was not a fluent Irish speaker but he was a vastly experienced and meticulous collector of the vernacular. Micheal J. collected many stories from my great uncle Johnny ‘Robin’, a brother of my grandmother Annie. However, Johnny has passed away in the late 1940s. There is no doubt whatsoever that Johnny knew what a Beacán Bearaigh was.

I have since come to the conclusion that the word Beacán Bearraigh is only conjured up in the mind when you are out walking and are suddenly confronted with one! For someone who doesn’t speak the language, perhaps it only springs to mind from a distant memory of a long past encounter. The type of encounter when, as a child, your granny points and says, “leave them alone, they’re only ‘oul Beacán Bearraigh”. It’s not something that rolls off the tongue sitting by the hearth even when a folklore collector asks the question about mushrooms. Why? Because they’re not mushrooms, they’re ‘Beacán Bearraigh!

Foraging in Ireland-Courses for Beginners

At least, the story does go to show that there is still some knowledge there to tease out. It’s just below the surface waiting to have the veil pulled back. We need to ask the questions of our fathers, mothers, aunts, and uncles.

We also have a responsibility to pass whatever we know down to the next generation.

I prefer to think that the art of foraging like the language has not been lost but simply forgotten. It’s deep down inside all of us, it’s tacit knowledge just waiting to be re-awakened.

When I learn about a new plant and observe it through the seasons, it’s almost like meeting an old friend. When I pass that knowledge on to someone else through one of my ‘introduction to foraging’ courses or ‘Foraging in the Foothills’ events, it just feels right. Supermarkets and pharmaceutical companies have only been with us for a very short time. On the other hand, that understanding of the natural world, what to embrace, and what to be careful around is in our DNA. Fathers passed it to sons, mothers passed it to daugthers and druids or sages passed it to villages for thousands of years. Something like that doesn’t just disappear in a few generations.

After all, each one of us, whether we come from the country, town or city has a successful line of foragers not that far back in our lineage. Otherwise, we just simply wouldn’t be here.

So, thanks to the three Annies who in their different ways spoke to me down the generations of ‘Beacán Bearaigh’. My great Grandmother, Annie ‘Robin’ McGuill of Cloughinnea. My aunt Annie Mc Coy from Cloughinnea / Tiffcrum and Annie Mc Donnell of Aughanduff.

Why the name Mountain Ways Ireland ?

When I chose the company name ‘Mountain Ways Ireland’, it was tipping my cap in two directions.

Firstly, and maybe the most obvious reason was that it spoke to my love for walking the mountains. There is a sheer beauty only to be found in the solitude of high places.

Secondly, it was a glance towards the ‘Old Ways’ of my ancestors. Those people who foraged, struggled, lived, laughed, loved, and died in these mountain valleys for thousands of years before me.

‘Foraging in the Foothills’ is much more than a plant identification journey.

If you would like to join me on one of our foraging or wild food experiences, check out our events calendar for all upcoming walks.

Escape – Embrace – Enjoy!

By Brian Hoey